Most developers never touch network programming at the socket level. Modern frameworks abstract it away. You call an HTTP library, and data appears. The underlying connection mechanics remain invisible.

But understanding sockets matters. They power every networked application. In my Computer Networks II course, I had the chance to build something that would expose these internals. The assignment was to create an FTP system from scratch.

I decided to go beyond the requirements. Instead of just building a command-line tool, I created a complete cloud storage suite with graphical interfaces. Both client and server. Each with GUI and console options.

What It Does

UCAB Cloud is a file transfer system built on the FTP protocol. The server runs on a configurable port and handles multiple clients simultaneously. The client connects, authenticates, and manages files remotely.

The server provides a desktop application where administrators start and stop the FTP service. They can manage users, set home directories, and monitor connected clients. Files and folders display in a visual browser.

The client application mirrors the server’s interface. Users connect with credentials, then navigate the remote file system. They can upload files, download files, create folders, rename items, and delete content. The interface shows the current path and file details.

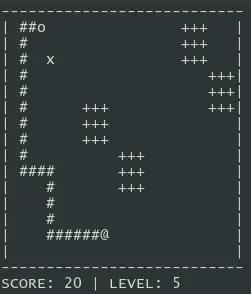

Both tools also have console versions for systems without graphical environments. The same functionality works through text commands.

Technical Deep-Dive

Building Sockets from Scratch

The entire network layer uses POSIX sockets directly. No networking libraries. No HTTP wrappers. Raw system calls handle every connection.

The socket implementation covers the complete lifecycle. Creating sockets, binding to ports, listening for connections, accepting clients, sending data, receiving data, and closing connections. Each step involves direct calls to the operating system.

The server uses TCP sockets for reliable data transfer. When a client connects, the server forks a new process to handle that session. This process isolation means one client’s problems cannot crash others. Each child process has its own socket descriptor and manages its own state.

FTP Protocol Implementation

The server implements core FTP commands. Authentication happens with USER and PASS commands. Navigation uses PWD, CWD, and LIST. File operations include STOR for upload, RETR for download, MKD for creating directories, and custom commands for rename and delete.

Passive mode allows clients behind firewalls to initiate data connections. The PASV command makes the server open a new port. The server calculates and returns the port number in the standard FTP format. The client then connects to this port for data transfer.

Binary and ASCII transfer modes both work. Binary mode transfers files byte by byte without modification. ASCII mode handles text files with line ending conversions. The TYPE command switches between modes.

Handling Multiple Clients

Concurrent connections require careful management. The main server process loops continuously, accepting new connections. When a client connects, fork creates a child process. The child handles all communication while the parent continues accepting new clients.

This forking model provides isolation. Each client gets dedicated resources. Memory, file handles, and state remain separate. A misbehaving client cannot affect others.

The shared user database presents a challenge. Multiple processes might read the same user file. The implementation keeps the file read-only during normal operation. Changes require administrative action through the manager interface.

Data Transfer Architecture

FTP separates control and data connections. The control channel handles commands and responses. The data channel transfers file contents and directory listings.

For downloads, the server reads the file in chunks. Each chunk sends through the data socket. The 2048-byte buffer size balances memory usage with transfer efficiency. Large files stream without loading entirely into memory.

Uploads work similarly in reverse. The server receives chunks and writes them to disk. The binary mode preserves exact file contents. Transfer completion triggers a confirmation message on the control channel.

Qt Quick Interface

The graphical interface uses Qt Quick with QML. This declarative language defines the visual structure. Components like file browsers, user cards, and navigation bars assemble into complete screens.

C++ classes expose functionality to the QML layer. The server manager starts and stops the FTP process. The file manager lists directories and handles operations. The user manager reads and modifies the credentials file.

Qt’s signal and slot mechanism connects these layers. User actions in QML trigger C++ methods. Results flow back through property bindings. The interface updates automatically when data changes.

The Material design style gives the application a modern look. Buttons, headers, and lists follow familiar patterns. Users navigate intuitively without learning new conventions.

User Authentication

Users authenticate against a simple credentials file. Each line contains a username, password, and home directory path. The server reads this file when processing login attempts.

After successful authentication, the server changes to the user’s home directory. All subsequent operations happen relative to this path. Users cannot navigate outside their designated area.

The manager interface provides user administration. Administrators create new users, set passwords, and assign home directories. Changes write back to the credentials file.

Challenges Faced

Socket programming reveals details that libraries hide. Error handling becomes complex. Connections can fail at any point. Timeouts occur. Clients disconnect unexpectedly. Each scenario needs explicit handling.

The FTP protocol has quirks. Response codes follow conventions but implementations vary. Passive mode port calculation requires specific formatting. Directory listings need particular structures for clients to parse them.

Coordinating the GUI with the network layer required careful threading. Network operations cannot block the interface. The server runs in a separate thread. Signals communicate between the network thread and the UI thread.

Testing distributed systems is difficult. Client and server must run simultaneously. Connection timing matters. Reproducing edge cases requires careful setup.

What I Learned

Building UCAB Cloud taught me what happens beneath network abstractions. Every HTTP request you make eventually becomes socket operations. Understanding this layer helps debug mysterious connection problems.

The project showed the value of protocol standards. FTP commands follow documented conventions. Clients expect specific response formats. Deviating from the standard causes compatibility issues.

Process management matters in server applications. Forking provides isolation but adds complexity. Resource cleanup, zombie processes, and signal handling all require attention.

Working at this level gave me appreciation for high-level frameworks. They handle the tedious parts. But knowing what they do underneath makes me a better debugger when things fail.