Back in 2019, I wanted to understand how games render graphics in the browser. Reading about game engines felt abstract. I needed to build something from scratch to make it click.

Tetris became my testing ground. The rules are simple enough to implement in a weekend. But the mechanics hide real complexity. Collision detection, piece rotation, row clearing - each feature forced me to think about how pixels move on screen.

I chose vanilla JavaScript and the HTML Canvas API. No frameworks. No libraries. Just the browser’s built-in drawing tools and my own code.

What It Does

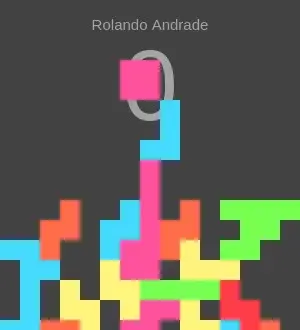

The game runs entirely in the browser. A 300x500 pixel canvas displays the play area. Five piece types spawn at random: the classic Z-shapes, L-shape, I-bar, and square. Each piece falls at a fixed interval.

Players control pieces with arrow keys. Left and right arrows move horizontally. Up and down arrows rotate the piece. When a row fills completely, it disappears and adds 150 points to the score.

The game ends when a new piece cannot fit on the board. Press Enter to restart.

Technical Approach

Shape Representation with Matrices

Each Tetris piece stores its shape as a 2D array. A 1 marks a filled block. A 0 marks empty space. The Z-piece looks like this in code:

[[1,1,0],

[0,1,1]]This matrix-based approach made rotation simple. Each piece holds an array of all its rotation states. Rotating just means switching to the next matrix in the sequence.

Collision Detection

Three types of collisions matter in Tetris. Floor collisions stop a piece at the bottom. Side collisions prevent pieces from going through walls or other blocks. Vertical collisions detect when pieces stack.

The game checks collisions by comparing block coordinates. When a piece tries to move, the code loops through all its blocks. It compares each position against the board boundaries and existing pieces. If any block would overlap, the move gets rejected.

Rotation adds extra complexity. A rotated piece might clip through walls or other blocks. The game detects this and automatically reverses the rotation.

Row Clearing Logic

After a piece lands, the game scans all affected rows. It counts blocks in each row from the piece’s top edge to its bottom. When a row has 15 blocks (the full width at 20 pixels per block), it triggers a clear.

Clearing a row means removing all blocks at that Y coordinate. Then every block above shifts down by one row. This cascades correctly because the game processes rows from bottom to top.

Game Loop

A simple interval timer drives the game. Every 200 milliseconds, the loop runs. It moves the current piece down, checks for collisions, and redraws everything.

Keyboard input triggers immediate redraws outside the normal loop. This keeps controls feeling responsive even at the slower fall speed.

Challenges

Canvas coordinate math. The Canvas API draws from the top-left corner. Y coordinates increase downward. This inverted system confused me at first. I had to mentally flip my coordinate logic.

Rotation edge cases. Rotating near walls caused pieces to clip outside the play area. The fix required checking bounds after rotation and reversing if invalid. This sounds simple but took several attempts to get right.

Breaking apart landed pieces. When a row clears, landed pieces might lose some of their blocks. The remaining blocks need to stay connected and fall correctly. Tracking partial pieces required rethinking how I stored block positions.

What I Learned

This project taught me canvas rendering fundamentals. Drawing rectangles, managing state, handling the animation loop. These basics show up in every browser game.

I also gained appreciation for matrix-based collision systems. Representing shapes as grids made complex operations like rotation much simpler than calculating pixel positions directly.

Most importantly, I learned that building from scratch beats reading documentation. The Canvas API made sense only after I used it to ship something real.