Servers fail. Hard drives crash. Network connections drop. When you store data on a single machine, you accept the risk of losing everything. Distributed systems solve this by spreading data across multiple servers. But coordinating those servers is harder than it sounds.

For a university distributed systems course, I built a book management system that replicates data across multiple servers. The goal was to explore how real-world systems maintain consistency when things go wrong. A single server corruption should not mean lost data.

What it does

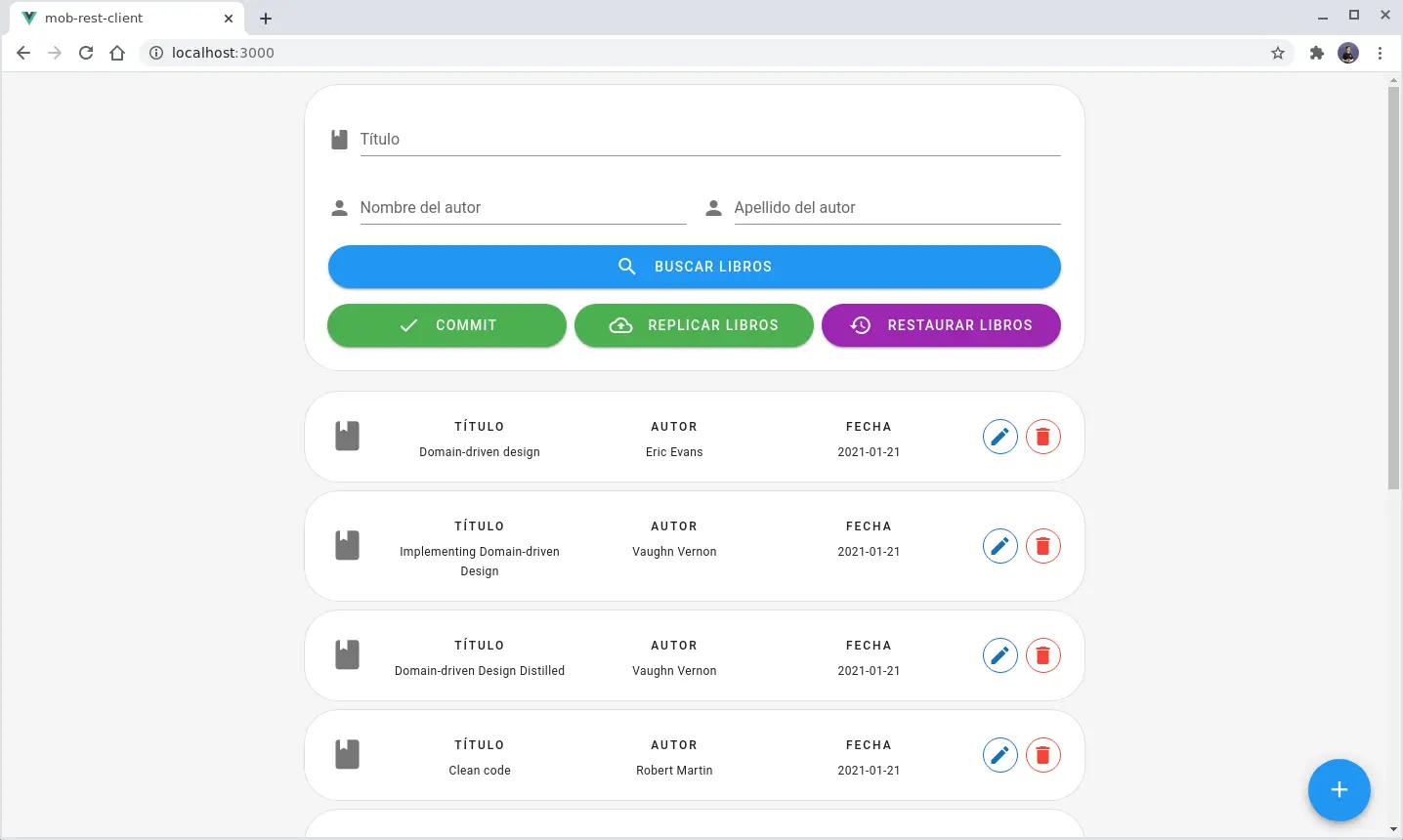

The system manages a collection of books stored as XML files. Users interact with a Vue.js frontend to create, read, update, and delete book entries. Behind the scenes, the data lives not on one server but on several.

When you save a book, the system replicates that data to all connected servers. When you restore data, the system queries every server and picks the most common version. This majority voting approach handles scenarios where one server has corrupted or outdated information.

The architecture has three main parts: the application server that handles REST requests from the client, a coordinator that manages the replication protocol, and multiple replicator servers that store copies of the data.

Technical deep-dive

Two-phase commit for replication

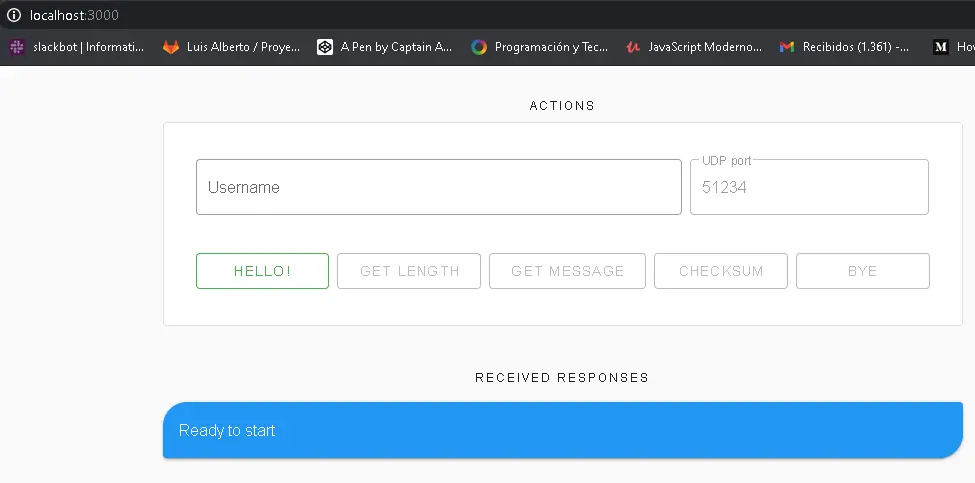

Data replication uses a two-phase commit protocol. When the application server wants to replicate, it sends a request to the coordinator. The coordinator then broadcasts a vote request to all connected replicator servers via WebSockets.

Each replicator votes either commit or abort. The coordinator counts the votes. If all replicators vote commit, the coordinator sends a global commit message. Otherwise, it sends a global abort. This all-or-nothing approach ensures that either all servers have the new data or none of them do.

After the global commit, replicators signal they are ready. Once all are ready, the coordinator sends the actual file data encoded in base64. Each replicator writes it to disk.

Majority voting for restoration

Restoration handles a different problem: what if the application server’s data is wrong? The coordinator asks all replicators to send back their stored data. Once all responses arrive, it compares them.

If all copies match, great. The system writes that version to the application server. If copies differ, the system uses majority voting. It picks the version that appears most often and uses that. This approach tolerates a minority of corrupted servers.

Mixed communication protocols

The system uses different protocols for different purposes. The Vue.js client talks to the NestJS backend over REST. Standard HTTP verbs handle CRUD operations on books.

Between backend servers, WebSockets handle real-time coordination. The coordinator maintains persistent socket connections to all replicators. This lets it broadcast vote requests and receive responses without the overhead of establishing new connections.

The separation makes sense. Clients make occasional requests. Servers need constant, low-latency communication during replication and restoration.

File-based storage

Each server stores data as an XML file on disk. Not a database. This was intentional. XML files are easy to inspect and corrupt for testing. They also made the replication logic simpler since the entire state is a single file.

The tradeoff is obvious. File-based storage does not scale. But for demonstrating distributed systems concepts, it worked well.

Challenges

Coordinating votes across multiple servers required careful state management. The coordinator tracks how many votes remain, how many were commits, and how many were aborts. If a replicator disconnects mid-vote, the system needs to handle that gracefully.

Testing was tricky. I needed multiple server instances running to verify the protocols. Manually corrupting XML files on specific servers helped validate the restoration logic.

Race conditions lurked everywhere. What if a replication request comes in while another is in progress? The coordinator rejects the second request until the first completes. Simple but effective.

What I learned

Building this system taught me why distributed consensus is hard. Even a simple two-phase commit has edge cases. What if the coordinator crashes after sending vote requests but before collecting all votes? Production systems need recovery mechanisms that this project skipped.

The majority voting restoration was satisfying to implement. Seeing the system recover correct data after deliberately corrupting one server felt like magic. But it only works when a majority of servers have correct data.

I also learned the value of choosing the right protocol for the job. REST for client-server communication. WebSockets for server-to-server coordination. Each has its place.