Game development tutorials often start with frameworks. Install Unity. Learn Godot. Pick up a physics engine. But these tools hide what actually happens when a ball bounces off a paddle. The abstractions help you ship games faster, yet they obscure the fundamentals.

I wanted to understand those fundamentals. In 2019, I decided to build one of the simplest games in existence using nothing but a canvas element and vanilla JavaScript. No libraries. No build tools. Just raw rendering and collision math.

Pong became that project. Two paddles, one ball, and a surprising amount of interesting problems hiding in plain sight.

What It Does

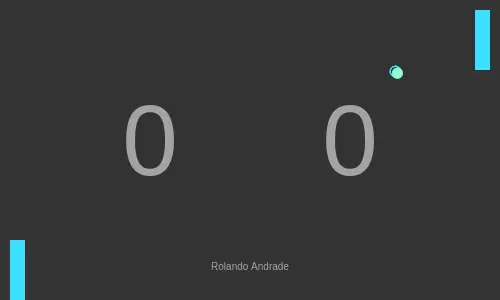

The game runs entirely in the browser. A 500x300 pixel canvas displays the playing field. The player controls the left paddle with arrow keys. An AI opponent controls the right paddle automatically.

A ball spawns in the center and bounces between the paddles. Missing the ball gives your opponent a point. Scores display as large numbers in the background. The ball speeds up slightly after each successful hit, raising the difficulty over time.

The game loops continuously at roughly 125 frames per second. Every frame clears the canvas, updates positions, checks collisions, and redraws everything.

Technical Deep-Dive

Canvas Rendering from Scratch

The HTML canvas provides a 2D drawing context. Every frame, the game fills the entire canvas with a dark background, erasing the previous state. Then it draws the paddles, the ball, and the score text on top.

I built reusable shape primitives for rectangles and circles. Each shape knows its position, dimensions, and color. The draw method handles all the context calls: setting fill styles, drawing paths, and stroking borders.

This immediate-mode rendering differs from retained-mode systems like the DOM. Nothing persists between frames. Every visual element redraws from scratch each tick. It sounds wasteful, but for simple games it works well and keeps the mental model clean.

Ball Physics

The ball moves by adding velocity to position each frame. Two velocity components control horizontal and vertical movement. When the ball hits the top or bottom walls, the vertical velocity inverts. The ball reflects and continues in the opposite vertical direction.

Paddle collisions are more interesting. When the ball contacts a paddle, the horizontal velocity inverts to send the ball back. But I also adjust the vertical velocity based on where the ball hit the paddle. Hitting near the edge sends the ball at a steeper angle. Hitting the center sends it straighter.

This angle calculation uses trigonometry. The offset between the ball and paddle center maps to a cosine function. The result creates a more dynamic game where paddle positioning matters beyond simply blocking the ball.

Each successful paddle hit also increases the horizontal velocity slightly. This progressive speedup prevents matches from lasting forever and adds tension as rallies continue.

AI Opponent

The right paddle tracks the ball automatically. The logic is simple: if the ball is above the paddle, move up. If below, move down. But pure tracking would be unbeatable.

Random offsets introduce imperfection. The AI compares positions with a small random buffer. Sometimes it starts moving too late. Sometimes it overshoots. This makes the opponent feel more human and gives the player a fighting chance.

The randomness scales with difficulty implicitly. Faster balls give the AI less time to react, and its imperfect tracking becomes more punishing.

Game Loop Architecture

A JavaScript interval fires every 8 milliseconds. Each tick runs the full game update: clear canvas, process AI movement, check collisions, update ball position, draw everything.

The player paddle responds to keyboard events outside the interval. Key presses immediately adjust the paddle position. This separation keeps input responsive even if rendering slows down.

Collision detection runs every frame before rendering. The ball checks its boundaries against both paddles and the walls. If a collision occurs, the ball’s velocity and position adjust before drawing. This prevents visual glitches where the ball appears inside a paddle.

Coordinate Geometry

Collision detection requires checking whether a circle intersects a rectangle. The ball tracks its center point and radius. The paddles track their top-left corner, width, and height.

For paddle collisions, I check if the ball’s edge crosses the paddle boundary while the ball’s vertical range overlaps the paddle’s vertical range. Both conditions must be true for a hit.

When a collision is detected, the ball position snaps to the paddle’s edge. This prevents the ball from getting stuck inside the paddle when moving fast.

What I Learned

Pong taught me that simple games hide real complexity. Bouncing a ball sounds trivial until you handle edge cases. What happens when the ball clips through a corner? How do you prevent tunneling at high speeds? These problems show up in every physics simulation.

Building without frameworks forced me to understand the rendering pipeline. Clear, update, draw. That cycle underlies every game engine. Knowing it made me appreciate what engines do and when to use them.

The AI logic also revealed how little intelligence games need. A few rules with randomness create the illusion of a thinking opponent. Players project intent onto simple patterns.