Many real-world problems have too many possible solutions to check them all. Finding the shortest delivery route. Scheduling shifts at a factory. Allocating resources across projects. The search space explodes as variables increase.

Traditional methods struggle with these problems. Brute force takes forever. Gradient descent gets stuck in local minima. And when some variables must be integers while others are continuous, the math gets harder.

Dr. Ebert Brea at Universidad Catolica Andres Bello was developing an extension to the Nested Partitions method. He needed someone to turn his mathematical theory into working code. I joined the project to build the implementation in C++.

What the Algorithm Does

The Mixed Integer Nested Partitions (MINP) algorithm solves nonlinear problems where some variables must be whole numbers. Think of choosing how many trucks to deploy (integer) while also deciding how much cargo each truck carries (continuous).

The algorithm works through four stages that repeat until convergence:

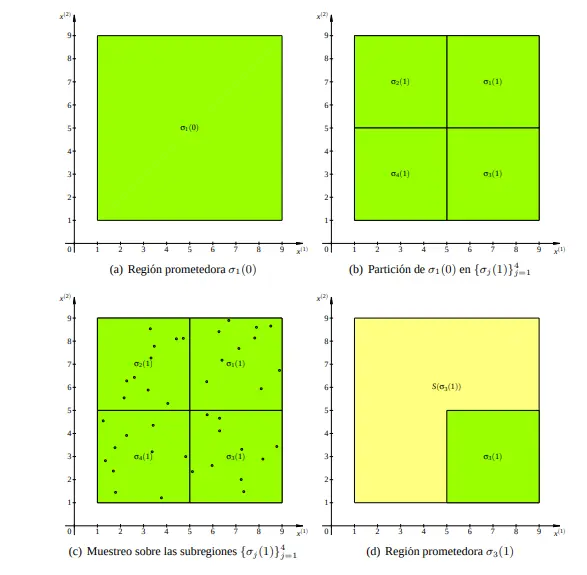

Partitioning - The algorithm divides the search space into smaller regions. Each partition contains a subset of possible solutions.

Random Sampling - Within each partition, the algorithm takes random samples. These samples estimate how good the solutions in that region might be.

Promising Region Identification - Based on the samples, the algorithm picks the most promising region. This region likely contains better solutions than the others.

Stopping Rule Verification - The algorithm checks if it should stop. If not, it focuses on the promising region and starts partitioning again.

Each iteration zooms in on better areas of the search space. Bad regions get abandoned. Good regions get explored more deeply.

The Mathematical Foundation

Nested Partitions belongs to a family of metaheuristic algorithms. These algorithms do not guarantee finding the best solution. But they find good solutions in reasonable time.

The method has a nice mathematical property. Dr. Brea proved convergence using Markov chain theory. The algorithm will eventually find a global optimum if given enough iterations. The proof matters because it separates rigorous methods from random guessing.

The extension to mixed integer problems added complexity. Integer variables cannot take arbitrary values. The partitioning scheme must respect this constraint. Each partition must contain valid integer combinations.

Building the Implementation

The C++ implementation needed to be fast. Academic research often runs experiments with thousands of iterations. Slow code means waiting days for results.

I structured the code around the four algorithm stages. Each stage became a separate module. This made testing easier. We could verify each stage independently before connecting them.

The random number generation required care. Bad randomness creates biased samples. Biased samples mislead the promising region identification. I used a well-tested generator and verified the statistical properties of the output.

Memory management also needed attention. Each iteration creates new partitions and samples. Without careful cleanup, memory usage grows unboundedly. I tracked allocations and freed memory as soon as partitions became irrelevant.

Handling the Stopping Rule

Knowing when to stop is hard. Stop too early and you miss better solutions. Stop too late and you waste computation.

Dr. Brea developed a new stopping criterion for the paper. The rule tracks how much the best found solution improves over recent iterations. When improvement stalls, the algorithm terminates.

Implementing this rule required tracking history. Each iteration records its best solution. The stopping rule examines this history and computes improvement rates. The threshold for stopping became a tunable parameter.

Running the Experiments

The algorithm needed validation. We ran it on standard benchmark problems from the literature. These problems have known optimal solutions. We could check if our implementation found them.

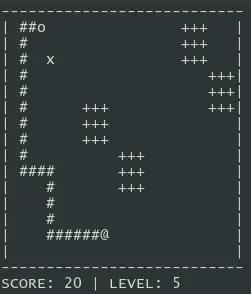

We also measured convergence speed. How many iterations does the algorithm need? How does this change with problem size? The experiments generated data that supported the theoretical claims in the paper.

I wrote scripts to automate the experiments. Each benchmark ran multiple times with different random seeds. The scripts collected statistics and generated tables for the publication.

What I Learned

This project showed me how academic research works. A good algorithm needs both theory and implementation. The math proves the method can work. The code proves it actually works.

I learned to read mathematical notation and translate it into code. The paper describes the algorithm in formal terms. Symbols and equations. Turning that into functions and loops requires careful interpretation.

Working with a researcher taught me patience. We iterated many times. Each revision of the paper might require code changes. Each experiment might reveal bugs or edge cases.

The paper was published in Tekhne, the engineering journal at UCAB. Seeing my implementation contribute to academic knowledge felt rewarding. The algorithm now exists not just as theory but as working software.