Libraries speak different languages. Not just Spanish, English, or French. Each library system has its own way of naming operations, structuring queries, and formatting responses. When you need to search across multiple library servers, this becomes a real problem.

Back in 2020, I was studying distributed systems. The professor presented a challenge: build a network where independent library servers could communicate despite using different internal protocols. The catch was that each server had to maintain its own terminology while still understanding requests from any client in the network.

This is where protocol translation becomes interesting. Rather than forcing every library to adopt the same language, I wanted to create a middleware layer that could translate between them.

What it does

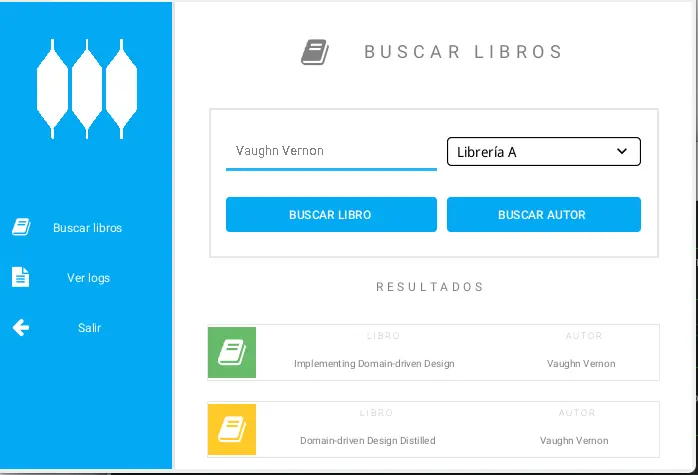

Libraries of the World is a distributed system where multiple library servers share their book catalogs. A user at one library can search for books across all connected libraries in real time.

The system handles three main operations:

- Search by title: Query all servers to find a specific book

- Search by author: Get all books by an author across the network

- Protocol translation: Convert between each library’s internal language and a common format

Each library server runs independently with its own book database stored in XML files. Clients connect through Java RMI and can query any server in the network.

Architecture

The system follows a clean separation between three main components: servers, clients, and a shared protocol layer.

The translation problem

Each library uses different command names. Library A might call a book search “Pedir Libro” while Library B uses “Buscar Título”. Without a common language, they cannot communicate.

I solved this with a two-layer translation system. The first layer defines a standard protocol inspired by Z39.50, the real-world library communication standard. Commands like “Get Title” and “Get Author” form this common vocabulary.

The second layer handles the translation. Each library has its own command set that maps between its internal language and the standard protocol. When Library A sends “Pedir Libro”, the middleware translates it to “Get Title” before forwarding the request.

Server design

Each server exposes a remote interface that accepts standardized commands. When a request arrives, the server:

- Receives the Z39-formatted command

- Translates it to the local library’s terminology

- Queries the XML database

- Translates the response back to Z39 format

- Returns the result to the client

The servers use synchronized request handling. When multiple clients query the same server simultaneously, a mutex ensures requests are processed one at a time. This prevents race conditions when reading from the shared book database.

Client middleware

The client side mirrors this translation pattern. When a user searches for a book, the client:

- Takes the search term

- Translates the request to Z39 format

- Connects to the remote server via RMI

- Receives the Z39-formatted response

- Translates it back to the local library’s terminology

This bidirectional translation means every library can use its preferred terminology while still participating in the network.

RMI communication

Java RMI handles the actual network communication. Each server registers itself in an RMI registry with a URL like rmi://192.168.1.100:3000/books. Clients look up servers by their network address and invoke methods as if they were local calls.

The configuration file defines all known libraries with their names and network addresses. This lets the client know where to send queries without hardcoding server locations.

Challenges

Command mapping complexity: Each new library type requires a complete command set mapping. Library A, B, and C each have their own translations. Adding Library D would mean creating another full mapping layer. A more flexible approach might use configuration files instead of code.

Synchronization overhead: The mutex on each server creates a bottleneck. Under heavy load, requests queue up waiting for their turn. For a production system, a connection pool or async processing would scale better.

Network discovery: Libraries must be pre-configured in a JSON file. There is no automatic discovery of new servers joining the network. A real-world system would need service discovery or a central registry.

What I learned

Building this system taught me how protocol translation works at a practical level. The Z39.50 standard exists because libraries faced this exact problem decades ago. Implementing a simplified version showed why such standards matter.

I also gained hands-on experience with Java RMI. While newer tools like gRPC have replaced RMI in most contexts, understanding remote method invocation fundamentals transfers to any distributed system.

The project reinforced the value of clean architecture. Separating the domain logic from infrastructure made it easy to swap implementations. The same translation layer could work over HTTP, sockets, or any other transport.