Simulation projects share a lot of common ground. They need to track time, schedule events, manage state transitions, and connect components together. Yet every time someone starts a new simulation, they rebuild these same pieces from scratch. The result is duplicated effort and inconsistent implementations.

I noticed this pattern while working on discrete-event simulations. The mathematical foundations stay the same across projects. What changes is the domain-specific behavior. A queue simulation and a cellular automaton both need event scheduling. They both need state management. They differ in how entities interact, not in the underlying mechanics.

This observation led me to build the General Simulation Framework. It provides the reusable infrastructure that every simulation needs. Developers focus on modeling their specific domain. The framework handles the plumbing.

What It Does

The framework supports discrete-event and discrete-time simulations. You define models, connect them into networks, and let the simulation engine advance time automatically.

Models are the building blocks. Each model has state, responds to inputs, and produces outputs. The framework provides base implementations that handle common patterns. You extend these bases and implement the domain-specific logic.

Dynamic systems organize models into networks. Models connect through weighted paths. When one model produces output, the framework routes it to connected models. This creates rich interaction patterns without manual event wiring.

The simulation engine orchestrates everything. It maintains a future event list, determines which models fire next, and coordinates state transitions. You can run simulations step by step or let them run to completion.

Technical Deep-Dive

The DEVS Formalism

The framework implements the Discrete Event System Specification (DEVS) formalism. DEVS provides a mathematical foundation for discrete-event simulation. It defines four key functions that models must implement:

- Internal state transition: How the model changes when it fires autonomously

- External state transition: How the model responds to inputs from other models

- Time advance: When the next autonomous event should occur

- Output: What the model produces when it fires

The framework also handles confluent transitions. These occur when a model receives input at the exact moment it was scheduled to fire. The default behavior executes the internal transition first, then the external. Models can override this if needed.

Event Scheduling

The scheduler uses a min-heap to track upcoming events. This gives O(log n) complexity for scheduling and O(1) for finding the next event. When multiple models have events at the same time, the framework fires them simultaneously.

Each scheduled entry tracks a model and its firing time. As simulation time advances, the scheduler decrements all pending times. This relative-time approach simplifies model implementation. Models specify how long until they fire, not absolute timestamps.

Path Routing

Paths between models can have weights. A weight of 1 means the output always flows through that path. Weights less than 1 create probabilistic routing. The framework selects paths randomly based on their weights.

This enables modeling scenarios like branching queues or probabilistic state machines. You specify the probabilities once during setup. The framework handles the random selection during execution.

Extensible Architecture

The framework uses inheritance strategically. Base types define the contracts. Concrete implementations provide specific behaviors. The dynamic system base is abstract. You extend it to create systems suited to your domain.

Report generators plug into the simulation engine. They receive outputs at each step. You can implement custom generators for logging, visualization, or analysis. The framework includes a default table-based reporter.

Entity management handles the creation and tracking of transient objects. Simulations often create and destroy entities during execution. The entity manager provides a clean interface for this lifecycle.

Example: Cellular Automaton

To illustrate the framework in action, consider a linear cellular automaton. Each cell has a binary state: alive or dead. Cells influence their neighbors at each time step.

The cell model extends the discrete-time base. It implements a state transition that copies input from its neighbor. The output function returns the current state. Each cell schedules itself to fire at regular intervals.

The automaton dynamic system creates cells and wires them together. The linear topology connects each cell to its right neighbor. The rightmost cell wraps around to influence the leftmost.

Running the simulation shows the automaton evolving. Patterns propagate through the cells. The framework handles all the event coordination. The model code focuses purely on the cellular automaton rules.

Learnings

Building this framework taught me the value of formal methods. DEVS provided a solid theoretical foundation. The mathematical definitions translated directly into code structure. This made the implementation cleaner and more predictable.

I also learned that good abstractions require iteration. Early versions exposed too much implementation detail. Later refactoring introduced cleaner interfaces. The final API hides complexity while remaining flexible.

The Python type system helped document intent. Type hints made the framework easier to understand and use correctly. They caught errors early and improved IDE support.

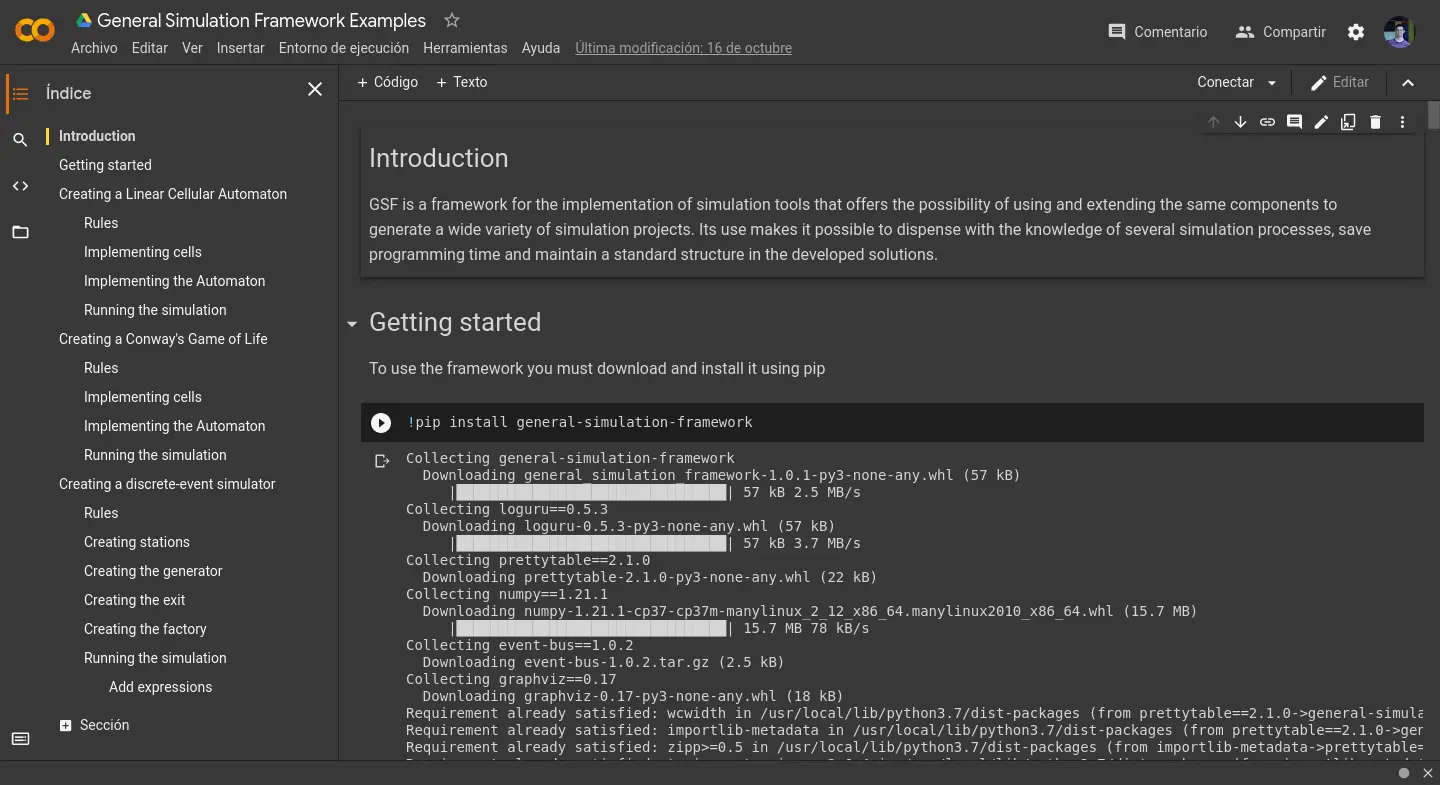

Publishing to PyPI forced me to think about packaging and documentation. Users need clear installation instructions and working examples. The Google Colab notebook lets people try the framework without local setup.

If you need simulation capabilities in your project, the framework is available on PyPI. Install it with pip and start modeling. The documentation covers the main concepts with runnable examples.