Learning data structures from textbooks is boring. You read about nodes, pointers, and memory allocation. The examples are always the same: add to list, remove from list, traverse list. None of it sticks.

I wanted a project that would make doubly linked lists feel real. Something where the data structure was not just an exercise but the foundation of actual gameplay. A Space Invaders clone for the Windows console seemed like the perfect challenge.

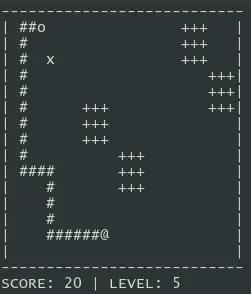

The result was Console Space, a simple shooter game that runs entirely in a command prompt window. No graphics libraries. No game engines. Just ASCII characters, keyboard input, and a lot of pointer manipulation.

What the Game Does

You control a ship at the left side of the screen. A grid of enemies advances from the right. You shoot bullets. Bullets hit enemies. Enemies disappear. The game loop runs until you win or the enemies reach you.

The ship renders as a special ASCII character. Enemies are small squares. Bullets are horizontal lines moving across the screen. Everything updates roughly ten times per second.

Movement uses the arrow keys. Spacebar fires bullets. The game reads keyboard input without blocking, so you can move and shoot at the same time.

The Data Structure Problem

Games need to track collections of objects that appear and disappear. Bullets spawn when you fire. They vanish when they hit something or leave the screen. Enemies start as a formation and get removed one by one as you destroy them.

Arrays would work, but they waste memory for inactive objects. You either allocate space for the maximum possible bullets or you deal with complex bookkeeping to reuse slots.

Linked lists solve this cleanly. Each bullet is a node. Firing creates a new node and links it. Hitting something removes that node and frees the memory. The list grows and shrinks dynamically.

For enemies, I used a doubly linked list. Each enemy node knows its previous and next neighbor. This makes removal simpler. When an enemy dies, you update two pointers and you are done. No shifting elements. No gaps to track.

How the Game Loop Works

The main loop runs forever. Each iteration does the same steps in order.

First, it clears the player ship from its old position. Then it checks for keyboard input. Arrow keys update the ship’s coordinates. Spacebar calls the firing function.

Next, it handles bullet movement. Every bullet advances one position to the right. If a bullet leaves the visible area, it gets removed from the list.

After bullets, the enemies move. They shift up and down in a pattern, slowly advancing toward the player. The movement variable tracks direction and triggers the leftward march.

Collision detection runs next. The game checks if any bullet occupies the same coordinates as any enemy. A hit removes both the bullet and the enemy from their respective lists.

Finally, everything gets drawn. The ship, all bullets, all enemies. Then the game sleeps for 100 milliseconds before the next iteration.

Rendering Without a Graphics Library

Drawing to a Windows console means moving a cursor and printing characters. The gotoxy function positions the cursor at any coordinates. Printing a character puts it there.

Clearing an old position is just moving to those coordinates and printing a space. This creates the illusion of movement: clear the old spot, print at the new spot.

The console is a 51 by 51 character grid. Each game object just needs x and y coordinates within that space. No pixel math. No sprite sheets. Just row and column numbers.

The Bullet List

Bullets use a singly linked list. Each node stores x and y coordinates plus a pointer to the next bullet.

Creating a bullet allocates a new node, sets its position to the ship’s location, and links it at the end of the list. A safeguard prevents rapid fire by checking if the last bullet has traveled far enough.

Updating bullets is recursive. The function walks the list, clears each bullet’s old position, draws it at the new position, and advances its x coordinate.

When a bullet goes off screen, it gets unlinked and deleted. The check happens before the update, so bullets never render outside the play area.

The Enemy Grid

Enemies use a doubly linked list. The extra pointer to the previous node simplifies removal. When an enemy dies, you adjust its neighbors to point past it.

The game initializes 25 enemies in a 5 by 5 formation. Each node gets assigned coordinates that position it on the right side of the screen. The list builds from front to back, linking each new enemy to the one before.

Movement follows a zigzag pattern. Enemies shift vertically for a few frames, then advance one column toward the player. A counter tracks when to switch direction. This creates the classic Space Invaders march.

Collision Detection

Finding hits means comparing every bullet against every enemy. The check function walks the enemy list looking for a matching position.

When a bullet and enemy share the same coordinates, both get removed. The bullet comes out of its list. The enemy comes out of its list. Memory gets freed.

The removal code handles edge cases. An enemy might be first in the list, last in the list, or somewhere in the middle. The doubly linked structure makes all three cases manageable.

What I Learned

Building this game taught me more about pointers than any classroom exercise. When your ship stops shooting because you forgot to update a link, you learn to trace memory carefully. When enemies disappear unexpectedly, you learn to debug list traversals.

The project also showed how simple building blocks create complex behavior. Doubly linked lists are a basic concept. But they enable smooth enemy removal. Smooth removal enables satisfying gameplay. The data structure choice matters.

Working without a game engine was instructive too. Modern tools hide so much complexity. Writing a game loop by hand, handling input without libraries, rendering with nothing but print statements - all of it builds appreciation for what frameworks do.

Console Space was a small project with a narrow scope. But it turned an abstract concept into something tangible. I could see the linked list working every time a bullet hit an enemy.