Learning data structures from textbooks can feel abstract. You read about linked lists, understand the theory, then forget it a week later. The concepts don’t stick because there’s no tangible outcome.

I wanted to change that. Back in 2019, I was studying linked lists in my computer science courses. Instead of just completing exercises, I decided to build something that would make the data structure feel real.

So I built a Snake game that runs entirely in the Windows console. No graphics libraries. No game engines. Just C++, the Windows API, and a linked list powering the snake’s body.

What It Does

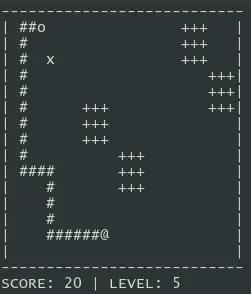

The game recreates the classic Snake experience in a text-based environment. You control a snake that moves around a 50x50 grid. Eating food makes the snake grow longer. Hitting the walls or your own tail ends the game.

The snake renders as asterisks on the screen. Food appears at random positions. Arrow keys control the direction. The game runs at a steady pace using Windows sleep functions.

It’s simple by design. The goal was never to build a polished game. It was to prove that I understood how linked lists work.

Technical Deep-Dive

The Linked List as a Game Mechanic

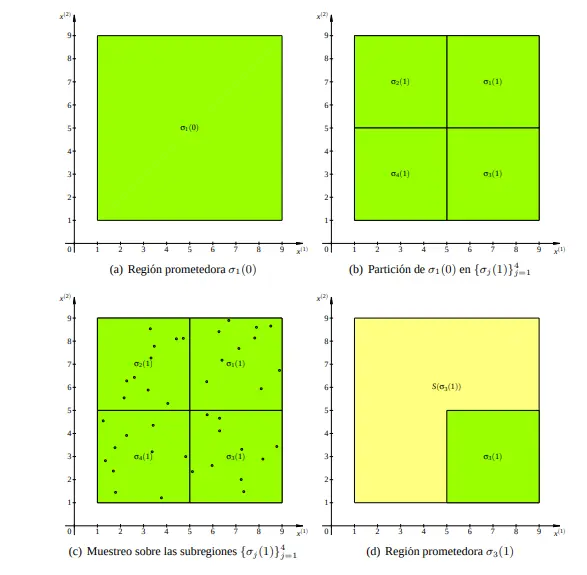

The snake’s body is a doubly linked list. Each node stores an x-coordinate, a y-coordinate, and a direction. The head of the list is the snake’s head. The tail is the last node.

This structure makes growth trivial. When the snake eats food, I create a new node and attach it to the tail. The position calculates based on the current tail’s direction. No array resizing. No shifting elements. Just one pointer update.

Movement propagates through the chain. The head moves first based on player input. Each subsequent segment inherits the direction from the segment ahead of it. This cascading update creates the characteristic snake motion.

Console Graphics Without Libraries

The Windows console provides cursor positioning through its API. I move the cursor to specific coordinates and print characters. Clearing the old tail position and drawing the new head position creates the illusion of movement.

This approach avoids redrawing the entire screen each frame. Only the changed positions update. It keeps the rendering fast enough for smooth gameplay.

Random number generation handles food placement. The game seeds the generator with the current time, then picks coordinates within the play area.

Collision Detection

Death happens when the head hits a wall or any body segment. Wall collision checks if coordinates exceed the boundaries. Self-collision searches through the linked list to see if the head’s position matches any body node.

The recursive search function walks through the list node by node. If it finds a match, the game ends. This linear search works fine for the snake’s typical length.

Input Handling

The game polls for arrow key presses using the Windows asynchronous key state function. A small guard prevents the snake from reversing into itself. You can’t go left if you’re already moving right.

What I Learned

Building this game taught me that data structures have practical applications beyond interview questions. A linked list isn’t just a theoretical construct. It’s a tool that models real problems elegantly.

The project also showed me the value of constraints. Working without game frameworks forced me to understand what happens at a lower level. Cursor positioning, timing loops, keyboard polling. These fundamentals matter.

Sometimes the best way to learn something is to build something with it.